Preventive Cure

Chronic Ambient Poisoning (CAP) is an anthropogenic habitat injury that manifests in humans. Poisoning is continuous or recurrent with peaks of varying magnitude and produces signs and symptoms that may be disabling for years before the detection of any consequent final common pathway diseases. As a diagnosis, CAP thus moves the focus of research and intervention up the causal web from death and end-stage disease to primary causes. Thus, it enables preventive cure. Due to the diversity of poisons; the diversity of genes and their impacts on metabolism; the diversity of end organ effects resulting from the poisoning process; and the diversity of lifetime combined and cumulative dosages of various poison “cocktails,” each case must be defined and investigated with an “N-of-1” study in which suspected causes are eliminated for long periods in hopes of effecting detoxification and resultant recovery and cure[1].

Chronic Exposure

With the ubiquitous dissemination of natural and synthetic chemicals and radiation that poison life and contribute to vitacide (e.g. extinction of evolved life), humans have developed new ailments analogous to those in other species such as birds, bees, amphibians, and insects[2]. Since the discovery of fire, and earlier, humans have been creating toxins that cause illness. One premodern example is nasopharyngeal cancer due to the combination of indoor smoky fires with Epstein-Barr virus exposure; another is lung disease, an occupational ailment of stonemasons, millers, bakers, coal miners, and others. The radical experiment of modernity[3] has led to many new chronic illnesses in workers[4], including: jaw cancer in women who painted clock hands with radium[5], testicular cancer in chimney sweeps[6], lung cancer and asbestos in dock workers[7] and cognitive delay in children due to lead paint[8].

Now that poisons have been disseminated through the wild and modified world[9], chronic and cumulative low-dose exposure is causing new kinds of ailments that cannot be comprehended within the modern worldview. These new hazards are also increasing rates of certain long-standing diagnoses. This applies to an unknown proportion of patients, perhaps especially those with disabling neurological conditions. Very little is known, partly because modern ideas and methods are integral to the problems of late modernity and thus unsuited for creating solutions[10]. Examples of this lack of traction include almost all studies to date of ME/CFS and of the health effects of non-ionizing radiation.

Diagnosis

All diagnosis is clinical, and therefore problematic with respect to a system that places uncertainty and ambiguity squarely in the Jungian shadow[11]—that is, that which we ignore. In the case of medicine, relegation to shadow entails referring patients to psychiatry for drugging that stops complaints. Doctors who are independent-minded, curious, and open may be better prepared to look into the shadows, in which case they will be stymied by constellations of symptoms that are not in the textbook and that make no sense within the modern frame. A clinically-derived causal model linked to etiopathogenesis, like the one presented here, can come only from the type of clinical research that has fallen out of favor and been quashed by false ideas of time efficiency (e.g. doing what is expected as quickly as possible while thinking as little as possible). This and information overload have obstructed development of a useful diagnostic gold standard[12][13]. There is thus no metric against which to evaluate potential biomarkers[14][15] as diagnostic tests. This is a problem as most “markers” have little or no diagnostic utility[12][13]. Fortunately, the N-of-1 self-study reported here[1] has provided an etiopathogenic model that is deterministic in one patient and that can serve as a model for further N-of-1 studies by other patients and their doctors[16][17][18].

Etiopathogenic Model

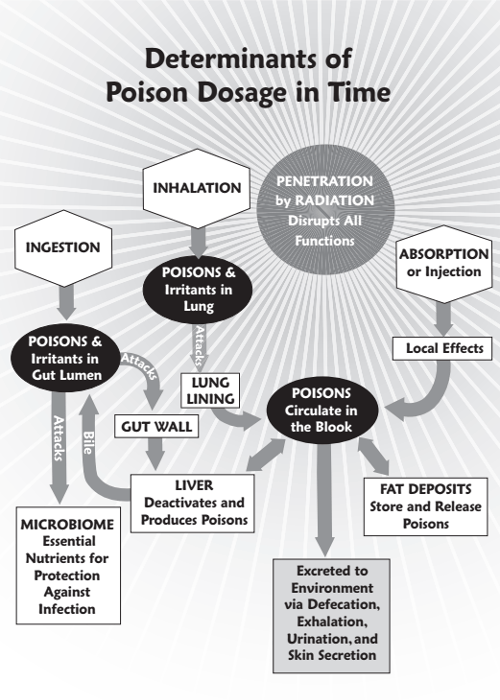

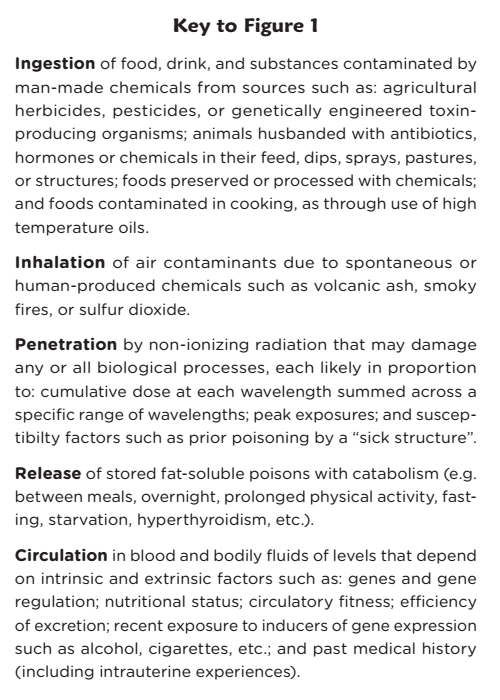

Poisoning in Time

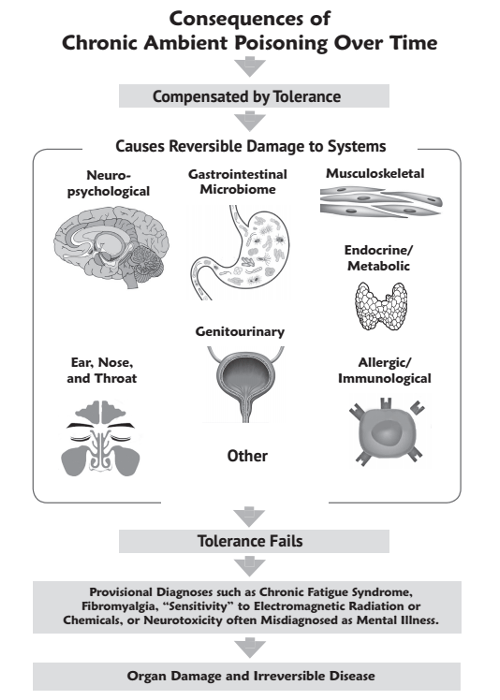

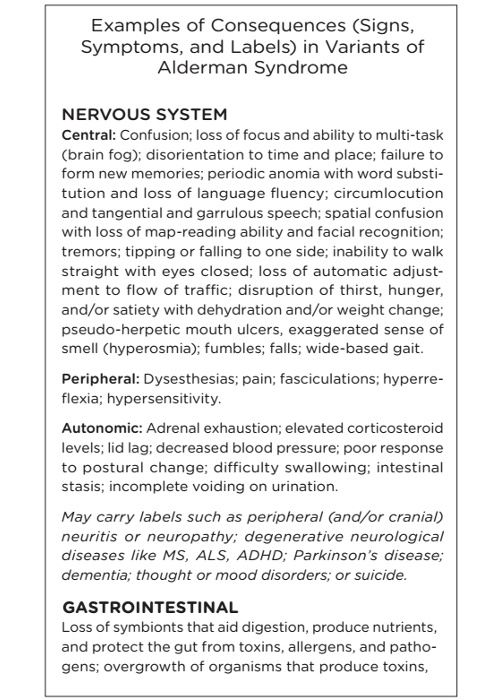

Consequences over Time

Research Methods

Modern Failures

The effects of ubiquitous exposures cannot be studied in the late modern way. Fortunately, the groundwork of emerging methods has already been laid for causal thinking, exposure assessment, outcome definition, and study design as well as self-patterning for discovery, as noted below.

Updating Causal Thinking

The context of epidemiology and public health practice is reasonably well-developed for infectious disease and in need of development for chronic illness. The incorporation of ecological frames by Mervyn Susser[19], with a historical perspective, revealed the complexity of useful causal thinking for this purpose, but his reliance on statistical modeling for the complex study of exposures with diverse metabolic consequences requires a body of clinical research that has ceased to develop. Computational models with one or two “main effects” and perhaps one “interaction” may work for overwhelming causal factors, such as smoking and coal mining in lung cancer, but are too simplistic to elucidate causal webs in daily life[10][20]. A quick comparison between the Krebs cycle, the electron transport chain, or the life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum and the average policy-oriented either/or statistical model will reveal that the latter is far too blunt an instrument to probe the unknown in intricate, dynamic biological systems that are active from the date of conception and before. Note that even the very simplest causal model includes agent, host, and environment, each of which is too complex for any simplistic model. In sum, data cannot yield solutions when problems demand knowledge and wisdom born of carefully-observed experience in vivo and in situ in free-living populations.

Assessment of Complex and Ubiquitous Exposures

While technology continues to dazzle[21], the thinking behind assessment for the purposes of health studies does not, especially with regard to non-ionizing radiation. Many investigators rely on electricians and other technicians who lack knowledge of biology and do the best they can with what they have. When investigators lack comprehension of etiopathogenesis and/or fail to comprehend physics, it is no surprise that studies of electromagnetism and its health effects ignore key questions of dosages and consequences[22]. Patients turn to the construction industry for protection, and contractors rely on products. Such solutions are decontextualized from biological reality as evolved prior to late modernity, and thus from the human body and from the as-yet barely considered body of life and its earthly substrates[23][24]. A Cal Tech study on the impact of geomagnetic fields illustrates the kinds of skills needed to assess the impact of the earth on humans.

In assessing chronic exposure as a cause of chronic illness, the brief catastrophic exposure that may be recognized by doctors of occupational medicine is unlikely to be missed by them, or to account for many cases of emerging conditions. That pattern of chronic exposure and consequences—such as the failure of tolerance[25] illustrated above, and the body of experiential learning assembled by building “biologists” and by the community at Greenbank[26][27]—point to doses of radiation varying by patterns of frequency and power over time, with lifetime effects cumulating, combining, and/or interacting with other sources of poison as well as with metabolic factors.

Metabolic factors and conventional food from distant sources[28] may have the greatest impacts on outcome, and so obscure the effects of radiation. Also important are failures of tolerance, pre-natal and early childhood exposures[29], microbiome effects[30][31][32], and the poison “cocktail,” its metabolites, and rates of absorption/production relative to rates of excretion and recovery. In sum, route, source, or other narrow exposure assessments are likely to miss effects regardless of how long or large or sophisticated the associated data collection may be[33][34][35][36][37]. Assessment should include all routes of exposure:

- Ingestion of conventional foods that include a variety of poisons, or contaminated organic food;

- Ingestion of unclean water (e.g. poisoned well or surface water);

- Inhalation of sulfur dioxide and other pollutants, especially in combination with allergens;

- Penetration by non-ionizing radiation in the electromagnetic range; and/or

- Absorption of household or workplace chemicals through the skin or other routes.

Note that because the dissemination of poisons has made them virtually ubiquitous, there is no normal—that is, no unexposed group—for comparison in any study. Only elimination studies can be effective. Note also that recovery takes years, not days.

Outcome Definition

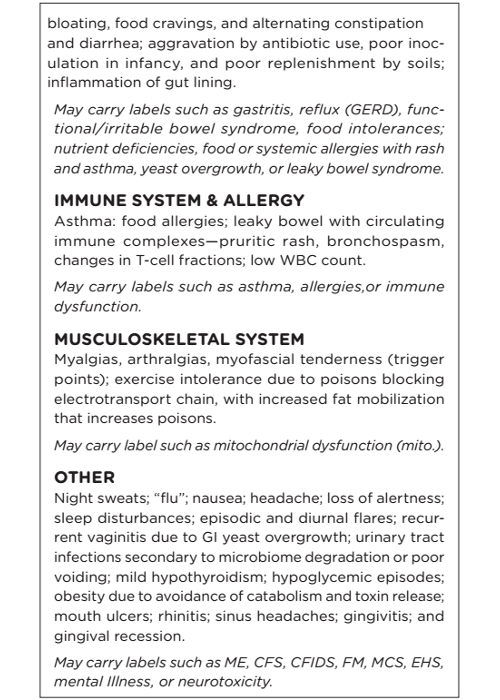

Cases of the emerging epidemics, especially ME/CFS (now subsumed by CAP), are notoriously difficult to count as they may present differently depending on poison cocktail, metabolism of poisons, end-organ sensitivity, and loss of tolerance. As per Ziem and McTanney[25], “multiple overlapping disorders” relate to a wide spectrum of poisons and a variety of process of “injury” such as: “neurogenic inflammation,” “kindling and time-dependent sensitization”, “impaired porphyrin metabolism” and “immune activation.” Given the repurposing of neurotoxic agents of biological warfare for application to crops and the widespread contamination of croplands and foods, neurotoxicity and related injury to organ function and structure begs examination. However, there is no reason to believe that cancer, obesity, cirrhosis, and other end-stage diseases are not catalyzed by chemical exposures. Self-report and clinical diagnosis with case series and N-of-1 interventions to arrest or reverse damage should be offered without delay. Note that there is no gold standard that can be used to form treatment groups for study, and there may never be one.

The Emerging N-of-1 Study Method

A deterministic study in a single patient may arrest or even, with early intervention, reverse disease. The “N-of-1” design has many, many advantages over all other prospective and retrospective designs[1], including the present clinical gold standard—the expensive and fallible randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial used for new pills. The advantages include:

- No outside funding needed.

- No wait required.

- Responsive to learning and resilient to frame and construct changes.

- No assumption that everyone is the same.

- No assumption that whatever preoccupies the investigator or the medical literature, or whatever expectations may be limiting them, are relevant to the case.

- The study subject has the perfect control subject—that is, the intervention and control subjects are one in the same person.

- The design controls for any number of unknown factors such as genes and modifiers of gene expression—free from the limits of statistical models that may suit policy analysis but do not suit biology, medicine, or continuous and resilient learning.

- A patient can—with enough clinical knowledge or a doctor who is free of top-down control and possessed of sensible, high-integrity curiosity—use this design over and over again until the problem is solved.

- The patient can revise the search for causes as soon as new knowledge is gained, and begin again immediately if need be.

- Patients can share what they learn if so inclined. However, the goal self-care and cure. There is no obligation to adhere to academic standards, or to develop the skills necessary to take care of others who may differ in cryptic ways.

In the reported self-study[1], a teacher of study design used this method intuitively and without the help of an expert governed by arbitrary and ill-fitting standards. A prepared clinician can help untutored patients do the same.

Self-Patterning for Action

The patient—supported by a doctor with a broad and deep knowledge base—is free to live the science of daily life in the way of Darwin[38] or Thoreau[39]. Careful, disciplined observation and integrity with education, insight, and perspective are required. Not all patients may be able to undertake discovery alone or even in a small group. Those who can may find cure, and their doctors can help, emergence. The modern era has seen disruption of ecological, human behavioral, and molecular processes that took eons to evolve, and which we must revise or restore in order to survive and thrive. With patient-led care and cure, there is unprecedented opportunity for personal transformation that begins at an individual’s core and extends outward into the bodies of the species, habitats, and life on earth. In this way, patients can care for and cure themselves as integral to life as a whole. This means of intensive and extensive care and cure integrates methods from the deep past of the species. The template for self patterning for action involves a sequence of steps, each of which requires prior self-patterning which may or may not have been taught at home or at school, or revised with experience. The sequence is as follows:

Priming –––> Stance –––> States –––> Strategies –––> Skills –––> Vision

Priming

Priming has been described in other contexts as “fire in the belly,” passion, drive, or motivation. It may arise from past experiences such as trauma or injustice, and may support the development of character and ethics. In this emerging paradigm it is the enduring fire and determination to care for and cure life on earth, including self and other humans. This is entirely a matter of your deepest desires as formed and informed by life, and which you can transform into life-saving action[40].

Stance

Your stance is your direction, momentum, attitude, face, and the like. In other words, it is the way that you meet life as you harness your priming and work toward your vision. It is helpful as you do this to view life on earth as sacred, e.g. as an “object” of wonder and inspiration.

State

States of being that are ideal for self-care that are distinct from those that are conducive to cure (see the Discovery course for more). If you are experiencing pain or suffering, or you are sharing care and cure through interbeing, it is wise to learn to recognize, enter, enhance, recover, and abide in care states for the sake of relief, well-being, and love of life. Methods for managing states of being were developed around the time of Hippocrates by the sramana (early yogis like the Buddha) and enhanced during the Indian Classical period. They are now useful in becoming and doing and thus in taking action to create a living future[41][42].

Strategy

Many strategies already exist for serving life: “No Impact Man,” the Seven Petal Living Building Paradigm, the Society for Ecological Restoration, Earthworks, Southern Oregon Land Conservancy, Lomakatsi, K5 Wild, the National Park Foundation, Home Rivers, 1% for the Planet, 1% for the Rogue, and many other local, national, and global sources of strategies and skills may work in your area and for you personally. With respect to cure states and discovery, you can learn more through through our on-demand courses.

Skill

Depending on your strategies, you may need to develop new skills such as assessing states of being or habitat biodiversity as well as restoring or rewilding life in your locale. This is too diverse to be prescribed and depends on your circumstances, abilities, passions, and ingenuity. The courses offered here can get you started.

Vision

Your vision is the goal that recedes as you work toward it, and that you change as you learn and as the river of life carries you forward. It is not feasible for everyone to have the same global vision, nor is it wise. If your vision of a living future is biologically possible, and is suited to your local resources and needs, it is not too soon to gather with others who wish to care for each life as all. It is conducive to hold a care state while researching local problems and delving into rich sources of ideas and methods such as theology, clinical medicine, field biology, and habitat restoration.

Self-support: Owning Your Own Placebo

The placebo was an artifact of modern study design: when internal relief and well-being happened apart from a drug under investigation, it biased expensive results. It was, from the researcher’s perspective, a confounder to be eliminated. This view does not support patients in taking charge of their innate abilities to reduce pain and suffering, which can be used to enhance care states and to avoid drug dependence and addiction. In the related courses, patients learn to “own” their ability to use awareness for easing pain.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Alderman, Beth (2019). Medical Detective. Ashland, OR: Future Medicine. ISBN: 978-1732111073.

- ^ Hance, Jeremy (2019). “The Great Insect Dying: A Global Look at a Deepening Crisis”. Mongabay. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Uglow, Jenny (2002). The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN: 978-0374194406.

- ^ LaDou, Joseph, ed. (2006). Current Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 4th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN: 978-0071443135.

- ^ Orci, Taylor (7 Mar 2013). “How We Realized Putting Radium in Everything Was Not the Answer.” The Atlantic. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ Waldron, H. A. (1 November 1983). “A brief history of scrotal cancer.” British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 40 (4): 390–401. doi:10.1136/oem.40.4.390.

- ^ “The Jones Act and Asbestos Exposure.” Maritime Injury Guide. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Canfield, R. L.; Jusko, T. A.; and Kordas, K. “Environmental lead exposure and children’s cognitive function.” Riv Ital Pediatr. 2005 Dec; 31(6): 293–300. PMID: 26660292.

- ^ Hardy, Don Jr. and Nachman, Dana (2013). The Human Experiment [documentary film].

- ^ a b Klein, Gary (2015). “Evidence-based Medicine.” In: This Idea Must Die: Scientific Theories that are Blocking Progress, John Brockman, ed. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN: 978-0062374349.

- ^ Jung, Carl; Campbell, Joseph, ed. (1971). The Portable Jung. New York: Viking Press. ISBN: 978-0670410620

- ^ Faraday, J. and Barrett, B. “Evolution of Diagnostic Tests.” In: Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 1281.

- ^ Weinstein, S.; Obuchowski, N. A.; Lieber, M. L. (2005). “Clinical Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests.” American Journal of Roentgenology 184: 14-19. Part of the Fundamentals of Clinical Research for Radiologists series.

- ^ Esfandyarpour, R.; Kashi, A.; Nemat-Gorgani, M.; Wilhelmy, J.; and Davis, R. W. (2019). “A nanoelectronics blood-based diagnostic biomarker for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).” PNAS 116(21): 10250-10257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901274116

- ^ Minerbi, A.; Gonzalez, E.; Brereton, N.; Anjarkouchian, A.; Dewar, K.; Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Chevalier, S.; Shir, Y. (July 2019). “Altered microbiome composition in individuals with fibromyalgia.” Pain. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001640. PMID: 31219947

- ^ Guyatt, G.; Sackett, D.; Taylor, D. W.; Ghong, J.; Roberts, R.; Pugsley, S. (1986). “Determining Optimal Therapy: Randomized Trials in Individual Patients.” New England Journal of Medicine 314: 889-912. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198604033141406.

- ^ Guyatt, G.; Sackett, D.; Adachi, J.; Roberts, R.; Chong, J.; Rosenbloom, D.; Keller, J. (1988). “A Clinician’s Guide for Conducting Randomized Trials in Individual Patients.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 139(6): 497-503.

- ^ Knottnerus, J. A.; Tugwell, P.; Tricco, A. C. (2016). “Editorial: Individual patients are the primary source and the target of clinical research.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 76(2016): 1-3.

- ^ Susser, Mervyn (1973). Causal Thinking in the Health Sciences: Concepts and Strategies in Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 978-0195015867.

- ^ Feinstein. Scientific Standards in Epidemiologic Studies of the Menace of Daily Life. Science 242(4883) 1257-63.

- ^ Holden, Emily (22 May 2019). “Is modern life poisoning me? I took the tests to find out.” The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ National Research Council (1993). “Standards and Guidelines for Exposure to Radiofrequency and Extremely-low-frequency Electromagnetic Fields.” In: Assessment of the Possible Health Effects of Ground Wave Emergency Network. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. ISBN: 978-0309047777. doi: 10.17226/2046.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (1 July 2019). “Wired Bacteria Form Nature’s Power Grid: We Have an Electric Planet.” New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Elhalel, G.; Price, C.; Fixler, D.; Shainberg, A. (2019). “Cardioprotection from stress conditions by weak magnetic fields in the Schumann Resonance band.” Scientific Reports: 1645. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36341-z.

- ^ a b Ziem, G. and McTanney, J. (1997). “Profile of Patients with Chemical Injury and Sensitivity.” Env Health Perspect 105(suppl 2): 417-36. doi: 10.1289%2Fehp.97105s2417. PMID: 9167975.

- ^ Kennedy, Pagan (21 June 2019). “The Land Where the Internet Ends.” New York Times. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Herzog, Werner (2016). Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World [documentary film].

- ^ Wilson, Bea (16 March 2019). “Good Enough to Eat? The Toxic Truth About Modern Food.” The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March, 2019.

- ^ Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Sass, J. B.; Engel, S.; Bennett, D. H.; Asa Bradman, A.; Eskenazi, B.; Lanphear, B.; Whyatt, R. (2018). Organophosphate Exposures During Pregnancy and Child Neurodevelopment: Recommendations for Essential Policy Reforms. PLoS Med 15(10); e1002671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002671.

- ^ Nagy-Szakal, D.; Williams, B. L.; Mishra, N.; Che, X.; Lee, B.; Bateman, L.; Klimas, N. G.; Komaroff, A. L.; Levine, S.; Montoya, J. G.; Peterson, D. L.; Ramanan, D.; Jain, K.; Eddy, M. L.; Hornig, M.; Lipkin, W. I. (2017). Fecal Mutagenic Profiles in Subgroups of Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Microbiome 5:44. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0261-y.

- ^ Yadollahpour, A; Jalilifar, M.; Rashidi, S. (2014). Antimicrobial Effects of Electromagnetic Fields: A Review of Current Techniques and Mechanisms of Action. J Pure Appl Microbio 8(5): 4031-4043 Oct 2014.

- ^ Akst, Jeff (1 June 2017). “Athletes’ Microbiomes Differ from Non-Athletes.” The scientist.com. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Toledano, M. B.; Smith, R. B.; Brook, J. P.; Douglass, M.; Elliott, P. (2015). “How to Establish and Follow up a Large Prospective cohort Study in the 21st Century – Lessons from UK COSMOS.” PLoS ONE 10(7): e0131521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131521.

- ^ Toledano MB1, Smith RB1, Chang I1, Douglass M1, Elliott P1. (2015). “Cohort Profile: UK COSMOS-a UK cohort for study of environment and health.” Int J Epidemiol 46(3):775-787. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv203.

- ^ Schraufnagel, D. E.; Balmes, J. R.; Cowl, C. T.; De Matteis, S.; Jung, S. H.; Mortimer, K.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Rice, M. B.; Riojas-Rodriguez, H.; Sood, A.; Thurston, G. D.; To, T.; Vanker, A.; Wuebbles, D. J. (2019). Air Pollution and Noncommunicable Diseases: A Review by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies’ Environmental Committee, Part 1: The Damaging Effects of Air Pollution. CHEST 155(2): 409-416. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.042.

- ^ Schraufnagel, D. E.; Balmes, J. R.; Cowl, C. T.; De Matteis, S.; Jung, S. H.; Mortimer, K.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Rice, M. B.; Riojas-Rodriguez, H.; Sood, A.; Thurston, G. D.; To, T.; Vanker, A.; Wuebbles, D. J. (2019). Air Pollution and Noncommunicable Diseases: A Review by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies’ Environmental Committee, Part 2: Air Pollution and Organ Systems. CHEST 155(2): 417-426. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.041.

- ^ Cassela, Carly (5 March 2019). “Scientists Detect ‘Shocking’ Drop in Male Fertility, and it’s Linked Back to Our Homes.” ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Darwin, Charles; Barlow, Nora, ed. (1958). The Autobiography of Charles Darwin. London: Collins.

- ^ Walls, Laura Dassow (2017). Henry David Thoreau: a Life. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN: 978-0226344690.

- ^ Alderman, Beth (2019). Medical Eldering. Ashland, OR: Future Medicine.

- ^ Alderman, Beth (2019). The Chronic Illness Owner’s Manual, Volume 1. Ashland, OR: Future Medicine.

- ^ Alderman, Beth (2019). The Chronic Illness Owner’s Manual, Volume 2. Ashland, OR: Future Medicine.